Ancient Microbes and Their Mysterious Rock Tunnels

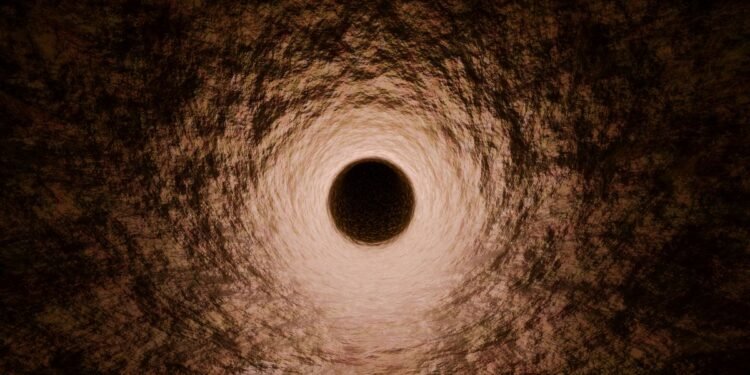

For eons, the deserts of Namibia, Oman, and Saudi Arabia have held secrets within their rocky landscapes. Geologist Cees Passchier, from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, recently stumbled upon a fascinating discovery: tiny, intricate burrows etched into ancient marble and limestone formations. These weren’t the work of modern-day creatures, but rather the enduring remnants of life that thrived millions of years ago. While the architects of these microscopic tunnels have long since vanished, their handiwork offers a tantalizing glimpse into a forgotten chapter of Earth’s history.

The investigation into these enigmatic burrows revealed compelling evidence of biological activity. Researchers meticulously examined fossilized burrows, and though no living organisms were found within, they did uncover biological material. This discovery strongly suggests that the formations were not the result of natural geological processes like weathering or abiotic chemical reactions.

Decoding the Evidence: What Could Have Bored Through Rock?

The existence of these burrows implies the presence of liquid water, a fundamental requirement for life as we know it. While the investigated areas are currently arid, they do experience occasional rainfall and dense coastal fog. Furthermore, geological records indicate that these regions were once significantly wetter, providing ample conditions for microbial life to flourish.

The question then arises: what kind of microorganisms possessed the ability to carve out these intricate tunnels? Several candidates come to mind:

- Bacteria: Known for their adaptability, bacteria can survive in extreme environments. Some species are endolithic, meaning they live inside rocks, potentially creating small cavities.

- Fungi: Certain fungi are capable of boring through rock. They achieve this by secreting digestive enzymes. While some fungi leave behind tubular structures, their typical growth pattern involves forming complex networks of filaments called hyphae, known as a mycelium.

- Lichens: These composite organisms, formed by a symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae or cyanobacteria, are also known to colonize and etch into rock surfaces.

Passchier and his team delved deeper to assess which of these microbial groups might be responsible.

Ruling Out Suspects: Why Fungi and Cyanobacteria Likely Aren’t the Culprits

While bacteria, fungi, and lichens are all plausible candidates for endolithic life, the specific characteristics of the discovered burrows helped researchers narrow down the possibilities.

Cyanobacteria: These photosynthetic organisms require sunlight to survive. The burrows were found to be significantly deep within the rock, suggesting that organisms that don’t rely on surface light were more likely to have created them. Cyanobacteria typically bore much shallower into rock formations.

Fungi: Although fungi can bore through rock, the observed burrows presented a challenge to this theory. Fungal burrowing often results in a complex, interconnected network of hyphae. The burrows in question, however, were remarkably parallel and evenly spaced, lacking the chaotic, ordered patterns typically associated with fungal mycelial growth. Furthermore, chemical analysis of the rock did not reveal the presence of the digestive agents that fungi would secrete.

The Case for Colonial Microbes: Evidence Points to a Collaborative Effort

The prevailing theory suggests that these burrows were not the solitary work of individual organisms, but rather the result of colonial activity. Several pieces of evidence support this hypothesis:

- Burrow Width: The burrows were found to be too wide to have been excavated by a single microbial entity. This points to a coordinated effort by a group of organisms.

- Growth Rings: The presence of what appear to be growth rings within the burrows further supports the idea of a multi-stage, potentially colonial, formation process.

- Calcium Carbonate Dust: Microscopic examination revealed the presence of calcium carbonate dust within the tunnels. This is a common byproduct excreted by microbes that inhabit and metabolize carbonate rocks like limestone and marble.

The Unseen Architects: Proof of Life, But No Definitive Identity

Despite the compelling evidence for biological origin, a definitive identification of the specific microbes responsible remains elusive. No fossilized organisms have been directly recovered from the burrows. However, the absence of these direct remains does not diminish the significance of the findings.

Thorough microscopic and geochemical analyses conclusively ruled out abiotic processes. The chemical composition of the rock samples taken from inside the burrows showed distinct differences from the surrounding rock, indicating that the material had been altered by living organisms.

Passchier and his colleagues stated in their published study, “As no known chemical or physical weathering mechanism can explain this phenomenon with the microstructural and geochemical observations presented here, and the micro-burrows form inside the host rock, we suggest that they are of biological origin.”

A Lingering Mystery: Could These Microbes Still Exist?

The discovery of these ancient micro-burrows opens up a captivating question: are the organisms that created them still present on Earth today, perhaps in other remote or undiscovered niches? It’s a tantalizing thought that these ancient tunnelers might still be quietly at work, carving out new subterranean worlds for future generations of scientists to uncover. The desert’s rocky facade continues to guard its secrets, but these microscopic tunnels offer a powerful testament to the enduring and often surprising resilience of life.