Farmers Face Financial Ruin as Paddy Prices Plummet

Farmers in Nepal’s Kailali district are grappling with significant financial losses as they are forced to sell their paddy harvests at prices well below the government-set rates. Many are finding themselves compelled to offload their produce to local traders at distressingly low figures, leading to widespread concern and hardship.

Bhagiram Chaudhary, a farmer from Padariya in Bhajani Municipality-3, exemplifies the plight of many. Waking up each morning, he is starkly reminded of his financial setbacks. “I had already sold 20 quintals of paddy to traders at a low price of Rs2,500 per quintal to cover immediate expenses for wheat farming,” he explained. “I still have 50 quintals of paddy stored at home. Now the price has dropped further to Rs2,300.” The fear of pests, particularly rats, damaging his remaining stored paddy adds another layer of anxiety. “I’m worried that the paddy at home will be ruined by rats. Now, even at a low price, I have no choice but to sell,” Chaudhary added, highlighting the desperate situation.

The government had established the purchase price for coarse paddy at Rs34.63 per kilogram through the Food Management and Trading Company Limited (FMTCL). However, the FMTCL has reportedly ceased purchasing paddy, citing that its allocated quota for procurement has been exhausted. This leaves countless farmers unable to sell their harvest at a fair price.

Ram Swarup Chaudhary, another farmer from Padariya and chairperson of the Pashupati Tole Development Committee, stated that approximately 200 farming families in his village are facing the same predicament, with their paddy stored in their homes. “I sold 20 quintals to a trader, but I still have 10 quintals left,” he shared. Collective efforts by the development committee to sell paddy to the Food Company proved unsuccessful.

The disparity between the government-set price and the market reality is stark. While the official rate stands at Rs34.63 per kg for coarse paddy, farmers are currently forced to accept rates as low as Rs23 per kg from traders. “We have no option but to sell paddy at the rate offered by the traders,” lamented Dhani Kumari Chaudhary, a farmer from Padariya. “We couldn’t sell it to the Food Company at all.”

Kanhaiyalal Dagaura, another farmer, voiced the deep irony of the situation. “Cultivating one hectare costs Rs10,000,” he stated. “When it’s time to sell, we have to sell at the price set by the traders. What could be more ironic for farmers than this?”

Declining Procurement Quotas Exacerbate Farmer Woes

A significant factor contributing to the farmers’ predicament is the reduction in paddy procurement quotas by the FMTCL. Last year, Kailali was allocated a quota of 55,000 quintals, and Kanchanpur received 15,000 quintals. This year, these quotas were drastically reduced to 35,000 quintals for Kailali and a mere 5,000 quintals for Kanchanpur.

Dipak Thapa, head of the provincial office of the FMTCL, acknowledged that the reduced quotas were met within approximately two weeks of the procurement process beginning. He explained that the decision to lower the quotas was based on the fact that the previous year’s allocation was not fully utilized. “Last year, paddy purchase did not meet the quota, so the government reduced it this year,” Thapa said.

However, farmers contend that selling to the FMTCL is a complex and often fruitless endeavor, even with the existing quotas. The primary issues they cite include:

- Insufficient Quotas: The allocated quotas are simply too small to accommodate the vast majority of farmers’ harvests.

- Lack of Purchase Guarantee: Even when farmers manage to deliver paddy to the Food Depot, there is no guarantee that it will be purchased.

- Need for Connections: With limited quotas, farmers often feel that personal connections or influence are necessary to successfully sell their produce to the Food Company.

- Delayed Payments: Payments from the FMTCL are reportedly not prompt, adding further financial strain on farmers who have already incurred expenses for cultivation and transportation.

“We transport paddy from afar at our own expense, but the employees sometimes return it saying it’s not clean,” Dhani Kumari Chaudhary shared, expressing frustration with the inspection process. This has led to suspicions among farmers that traders are colluding with the Food Company, buying paddy from them at low prices and then selling it to the FMTCL at higher rates.

FMTCL’s Procurement Figures and Market Strategy

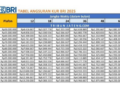

Despite the farmers’ struggles and the reduced quotas, Thapa, the provincial head, presented figures suggesting that the FMTCL had purchased more paddy than the initial allocations for Kailali and Kanchanpur. He stated that while the combined quota for these districts was set at 40,000 quintals, the company ultimately purchased 45,824 quintals. Specifically, in Kailali, the quota was 35,000 quintals, but 38,948 quintals were purchased. In Kanchanpur, the quota was 5,000 quintals, and 6,876 quintals were bought.

Nationwide, Thapa noted that out of a total quota of 700,000 quintals last year, only 120,000 quintals of paddy were purchased. This year, the national quota was increased to 170,000 quintals.

The FMTCL’s operational model involves purchasing paddy, processing it in its own mills, and then distributing the resulting rice, primarily to remote areas. However, the company’s strategy also includes purchasing rice directly from traders through tenders, especially when its own paddy procurement falls short of meeting demand. Thapa indicated that even with an anticipated purchase of only 38,000 quintals of paddy this year, the rice demand would be met through these tender purchases from traders.

This practice, farmers allege, fosters a situation where the FMTCL’s reliance on traders, coupled with the limited procurement from farmers, creates a cycle of low prices for producers and potentially inflated costs for consumers.

The provincial office of the FMTCL stated that it distributes rice across the far-western region through a network comprising five branches, two depot offices, and 60 sales centers spanning nine districts.

Meanwhile, agricultural data from the Kailali Agricultural Knowledge Center, as reported by Ghanashyam Chaudhary, its head, indicates a significant paddy cultivation in the district. This year, paddy was cultivated on 68,541 hectares in Kailali, yielding an estimated 308,434 tonnes of produce. This substantial harvest underscores the magnitude of the crisis faced by farmers who are unable to realize a fair return on their labor and investment.